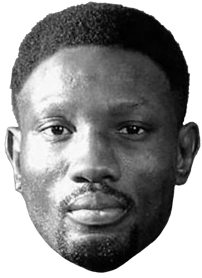

Pernell Whitaker (born January 2, 1964) is an American

former professional boxer and current boxing trainer. He won a silver

medal as a lightweight at the 1982 amateur World Championships, followed

by gold at the 1983 Pan American Games and 1984 Olympics. In his professional

career, Whitaker won world titles in four different weight divisions.

During his career he fought a multitude of world champions such as

Julio Cesar Chavez, Oscar De La Hoya and Felix Trinidad. For his achievements,

Whitaker was named the 1989 Fighter of the Year by The Ring magazine.

Whitaker is a former WBA light middleweight champion, WBC welterweight

champion, IBF light welterweight champion, WBC/WBA/IBF and NABF lightweight

champion, and was heralded as one of the top five lightweights of

all time.

After retiring, Whitaker returned to the sport as a

trainer. Among his trained boxers are Zab Judah, Dorin Spivey, Joel

Julio and Calvin Brock. In 2002, The Ring ranked him tenth in their

list of "The 100 Greatest Fighters of the Last 80 Years". On December

7, 2006, Whitaker was inducted into the International Boxing Hall

of Fame, in his first year of eligibility.

Fighting style

Whitaker

was a "southpaw" (left hand dominant) boxer, known for his outstanding

defensive skills and for being a strong counterpuncher. He was not

an over-powering hitter on offense but applied a steady attack while,

at the same time, being extremely slippery and difficult to hit with

a solid blow.

Amateur career

Whitaker had an extensive amateur

boxing career, having started at the age of nine. He had 214 amateur

fights, winning 201, 91 of them by knockouts, though he says that

he has had up to 500 amateur fights. He lost to two-time Olympic Gold

medalist Angel Herrera Vera at the final of the World Championships

1982 but beat him four other times, notably in the final of the Pan

American Games 1983 in Caracas. He crowned his amateur career with

an Olympic Gold Medal in 1984.

Professional career

Lightweight

In

just his eleventh and twelfth pro bouts, Whitaker beat Alfredo Layne

on December 20, 1986 and former WBA Super Featherweight title holder

Roger Mayweather on March 28, 1987. Whitaker won both bouts before

hometown crowds at the Norfold Scope, less than a mile from where

he lived as a child in a Norfolk housing project. Whitaker would fight

nine times in the Scope arena during his career.

On March 12,

1988, he challenged Jose Luis Ramirez for the WBC Lightweight title

in Levallois, France, He suffered his first pro defeat when the judges

awarded a split decision to Ramirez. The decision was highly controversial,

with most feeling that Whitaker had won the fight with something to

spare. In his 1999 edition of the 'World Encyclpedia fo Boxing,' Harry

Mullan stated that the decision in this bout was "generally considered

to be a disgrace." To date, the decision is rated at or near the top

of many boxing observer's "worst ever boxing decisions" lists.

Undisputed

Champion

Whitaker trudged on, winning a decision over Greg Haugen for

the IBF Lightweight title on February 18, 1989, becoming the first

boxer to knock Haugen down by dropping him in the sixth round. He

then added the vacant WBC belt by avenging his loss to Ramirez on

August 20.

Now a champion, Whitaker proceeded to dominate boxing's

middle divisions over the first half of the 1990s. In 1990, he defended

his Lightweight title against future champion Freddie Pendleton and

Super Featherweight Champion Azumah Nelson of Ghana. On August 11,

1990, he knocked out Juan Nazario in one round to win the vacant The

Ring and WBA titles, becoming the first Undisputed Lightweight Champion

since Roberto Duran. His highlight of 1991 was a win over Jorge Paez

and a fight against European Champion Poli Diaz that ended in another

win.